Barabbas' version: analysis of a major terror attack in Rome, A.D. 64

Our correspondent reports from the great city of the Caesars.

A few months ago, on 19th July of the tenth year of divus Nero Claudius Caesar Augustus Germanicus, DCCCXVII a.U.c.,1 a raging fire destroyed large swathes of the city of Rome. To undiscerning eyes it looked like any of the previous fires that periodically plagued the overcrowded metropolis, just bigger. Real estate developers had made a habit of cutting more than one safety corner, twisting the building regulations at will. And the ediles officers that were meant to oversee them did not mind to look the other way in exchange for a kickback or a nice beachfront house on the Gulf of Naples. When the shoddy developments were high rise apartment blocks destined to house poor people and recent immigrants from the periphery of the Empire, fire risk was a design feature, not a bug. But this fire was unusually devastating: after a week of unrelenting inferno, it wiped out 10 out of 14 neighbourhoods of the city, including the portion of the Forum where the senators lived and worked and even of Nero’s own palaces between the Palatine and Esquiline hills.

The loss of life was appalling, a real catastrophe watched live by tens of thousands of people, that is, at least those who could escape on the hills overlooking the Suburra and other affected neighbourhoods.

Nevertheless, the state security apparatus and the emperor Nero himself — with most of the mainstream media in tow — were quick to point the finger towards an obscure sect of Middle-Easterners practicing a notorious fundamentalist religion: the so-called Nazarenes or Christians.

A minority of investigative journalists noticed some inconsistencies in the official reconstruction and suspected instead that the Emperor himself and the Pretorian Intelligence Agency (PIA, a.k.a. speculatores) had a hand in the tragedy. But the sceptics soon divided themselves in the quarrelling LHOP vs MHOP camps (Let it/Made it Happen On Purpose) and were quickly dismissed by the public as hazed conspiracy theorists.

The official explanation was definitely more parsimonious and it didn’t take a great effort to persuade the public: everybody despised those Levantines. Besides, they had a proven record as terrorists and a specific motive.

Since this is a rigorous analysis, we will not refer here the racists slurs that the tabloid press was so keen to publish about the main suspects. Therefore, we will quote an influential analyst and historian, a buttoned-down fellow at the Consilium Relationibus Exterioribus who qualified the Christians as “a sect despised by all because of their malfeasances.” Here’s how he summarises the aftermath of the fire:

igitur primum correpti qui fatebantur, deinde indicio eorum multitudo ingens haud proinde in crimine incendii quam odio humani generis convicti sunt. 2

Translating from the original Latin for our Greek speaking readers in the Old World: “shortly afterwards we arrested the first group of those towelheads that infested our capital. After some waterboarding session, they confessed to their conspiracy and crimes and started to sing like nightingales. This led to further arrests, on a massive scale actually. At some point the security agencies suspected that perhaps some people were just snitching on the neighbours they had a feud with, to get rid of them, but we had to cast the net wide nevertheless. Besides, everybody loathed those foreigners, because we knew that they hated humankind.”

‘Hatred for the humankind’: the great historian put here in formal, scholarly terms what Nero himself had said on the heat of the moment: “they hate us, they hate our freedom.”

As for the motive, we will have to remember that the so-called Christians were a sect of the religion that originated among the Israelites living in the lands called Judaea, Galilea, Samaria, Idumea, Perea, etc. Judaea in particular, with the main city of Jerusalem, the seat of the great Temple, was under direct Roman rule, something that the Israelites resented deeply. More specifically, Pontius Pilate, the Roman governor of Judaea some thirty years before, had executed by crucifixion the founder of the sect, one Yeshua heNozri, a preacher, miracle worker and would-be King of the Jews, a crime punishable under the Lex Julia de maiestate (empires always need to find legal excuses to get rid of rowdy, rebellious provincials). Despite public protestations of peace, love and reconciliation from the official representatives of the Nazarenes-Christians, Agency’s analysts think that some members of the movement have joined ranks with other terrorists threatening Roman national security (these call themselves qana’im, better known as zelotes in Greek or sicarii in the Roman tabloid press).

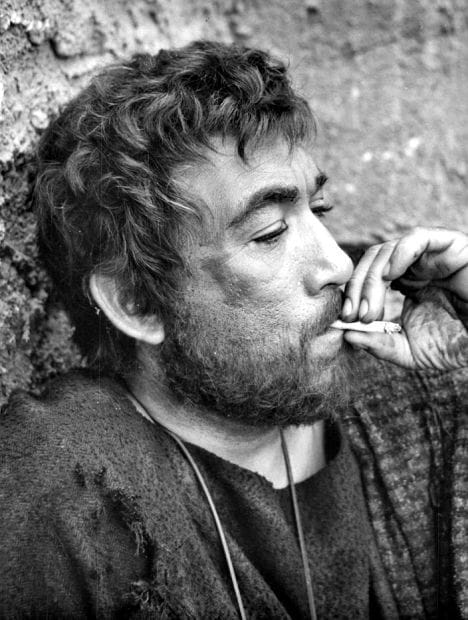

[agent provocateur caught in the act]

From the very beginning of direct Roman rule over Judaea in the thirty-seventh year of Caesar Augustus’s victory over Anthony at Actium, the inhabitants started rebelling under the stupendous contention that only their God is Lord over their land and they owe their allegiance only to Him. More critically for Rome’s coffers, they stubbornly refuse to pay tribute to Rome, and threaten or kill any one of their people who does. And they quickly resorted to terrorism. This is how one of the Agency’s assets (a brilliant fellow from an influential Jerusalemite family) describes the development:

[they] slew men in the day time, and in the midst of the city; this they did chiefly at the festivals, when they mingled themselves among the multitude, and concealed daggers under their garments, with which they stabbed those that were their enemies; and when any fell down dead, the murderers became a part of those that had indignation against them; by which means they appeared persons of such reputation, that they could by no means be discovered. The first man who was slain by them was Jonathan the high priest, after whose death many were slain every day, while the fear men were in of being so served was more afflicting than the calamity itself. 3

The security expert Salicus Lacertus Felsinus deems this to be the first definition of terrorism on the record. The chief suspect of masterminding the heinous terrorist attack is the notorious terrorist Ben Abba, a spoiled, rich rascal from a wealthy priestly family (as can be inferred from his Aramaic patronymic, Barabbas, literally: son-of-a-father, that the Florentines translate as figlio di papà), complete with the mystic delusions and fascistic instincts of his class. He started by attacking what he and his organisation — Ha’qannaim — considered traitors and sinners. These are the members of the priestly aristocracy belonging to the Sadducean party that collaborate with Rome as the local elite administering the domestic affairs of Judaea, especially religious matters, in a classic colonial scheme of indirect rule. After being captured in the aftermath of a targeted assassination in Jerusalem, Barabbas flipped after the application of moderate pressure. The PIA station chief assigned him a double task for his collaboration with Rome. First, he and his organisation had to keep pressuring the priestly aristocracy. In fact, those rich priests in their fancy robes were always scheming against Rome behind their facade of cordial cooperation. Beyond moral judgements inappropriate for a sober scientific analysis, the behaviour of this predatory colonial elite can be explained by their peculiar security predicament: hated by the populace as collaborators and exploitative landowners; mistrusted by Rome; threatened by the heirs of the royalist Herodians, eager to recover their position as privileged Roman clients.

As second task, the Jerusalem station chief asked Barabbas to infiltrate and inform about Yeshua heNozri and his movement. Agency’s assets had previously gathered intelligence that the followers of the Galilean (also called Nazarenes from his birthplace) were a rather heterogeneous group — comprising even several women and despised tax collectors, if you can picture that — but crucially including some extremists of the “fourth philosophy” (see the reports drafted by the PIA’s asset quoted above) also called the zealots or qana’im in Aramaic. Thanks to the intelligence provided by Barabbas the Agency eventually reached the conclusion that the Nazarene’s movement posed a non negligible security threats to Rome’s position in the Middle East and they dispatched Yeshua heNozri quickly without much fanfare before his movement could grow further. This seemed to have settled the matter.

[agent provocateur taking a break]

After several years as a reliable Agency’s asset Barabbas started behaving oddly. He got closer with some members of the Galilean’s movement that he had befriended before.4 While the leaders of the movement had learned their lesson and let politics alone (give or take some weird ideas on collective property), among their ranks dissent was brooding. A growing number of Nazarenes hotheads were not persuaded by the peace&love (and loyalty to Rome) doctrine espoused by one of the new leaders of the sect, one silver-tongued Saul, a Roman citizen by the way. In their hatred for Rome and the priestly aristocracy they naturally established operational and ideological linkages with the other phanatiques that had been active in Judaea since the time of Simon of Galilee and his “fourth school.” Besides, they sought revenge for the execution of their leader. First they joined Barabbas’ organisation in killing and kidnapping several members of the quisling Sadducean elite. But that was only the first stage of their strategy. In the language used by the terrorists, they wanted to bring the struggle from the “near enemy” (the corrupt priestly aristocracy) to the “far enemy,” Rome itself.

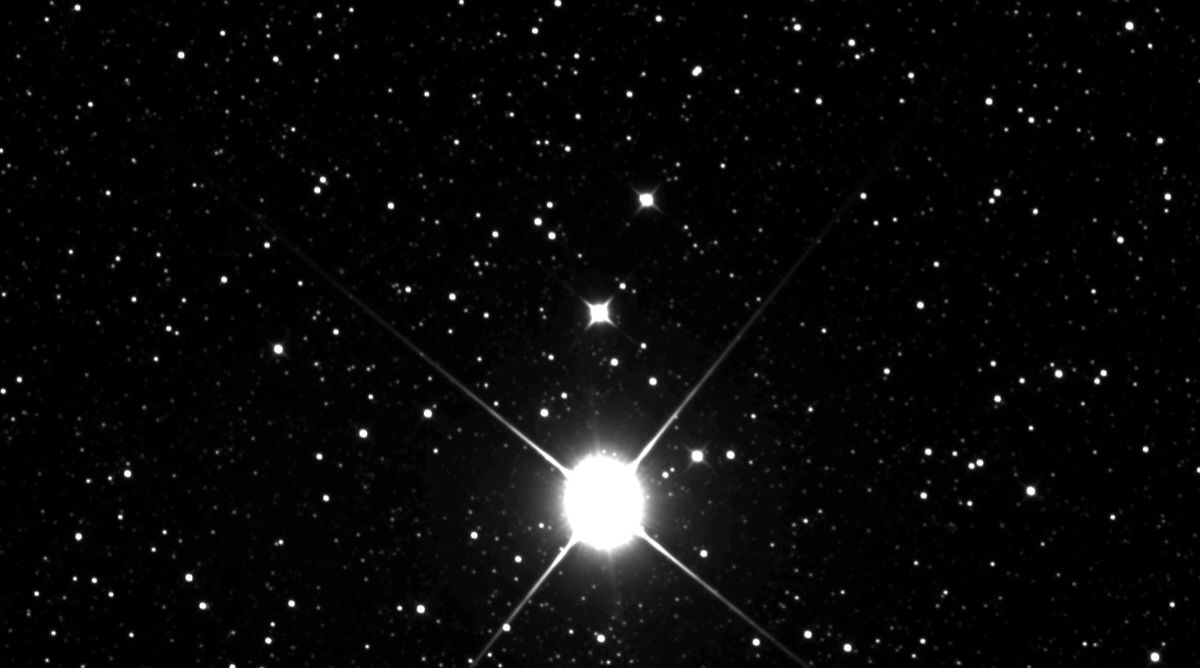

The phanatiques accelerated their preparations after their new respected leader in Jerusalem, one of the brothers of the founder himself, one Jacob called the Just, was captured and executed by the high priest. This was clearly a miscarriage of justice and judicial murder, because the high priests do not have the authority to carry out any death sentence. But the high priest Ananus ben Ananus is a sly operator and can count on the weight of one of the most powerful priestly-aristocratic families behind his back. He took advantage of the death of the incumbent Roman governor (Porcius Festus) and had Jacob the Brother of the Lord executed by stoning before the replacement arrived. The new governor, Lucceius Albinus, dismissed Ananus from office without much ado, but the damage was done. The phanatiques blamed Rome for the killing of their leaders: Yeshua first and now his own brother. Perhaps this was because the house of Ananus had been such a loyal ally of Rome, holding the Roman-appointed high priest office for almost four decades since the start of the Roman direct rule over Judaea. But the detail that aroused the hotheads among the sect of the Nazarenes is that their founder had been killed by a well coordinated plan conceived and carried out by the roman governor Pontius Pilate and Ananus the Elder (never mind that the high priest at that time was Ananus son-in-law, one Joseph Caiaphas; it was the old man who pulled the strings, and quite openly at that, even presiding over official meetings). Things soured further between this powerful aristocratic clan and the phanatiques when these killed Jonathan, one of Ananus’ sons, and former high priest himself, in the last year of Claudius. So the killing just two years ago of the leader of the Nazarenes, one James, the very brother of the founder of the sect, by yet another of Ananus’ sons is as much a political issue, a class conflict, and a family feud. These terrorists in the meantime established several cells in the slums of Rome where their countrymen lived and spread political propaganda couched in apocalyptic visions predicting that the wrath of their God in the form of a raging inferno on the day of the rising Sirius (19th July, a widespread Levantine belief) would reduce the city to ashes. In all those oracles there was a constant refrain: “Rome must burn” and the phanatiques tried very hard to hasten the eschaton.5 Since then the Agency had picked up signals here and there that something really big was afoot, but no one could connect the dots.

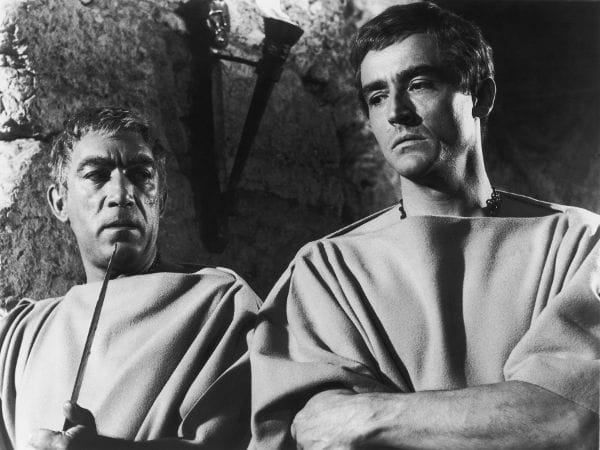

[agent provocateur and young radicalised recruit conspiring in the catacombs]

The exact dynamic of the city-wide arson is not clear yet. A major commission of inquiry appointed by the Senate is still working on the case. It seems that some of the most disciplined and bloodthirsty among the phanatiques, often called sicarii from their weapon of choice for terror-spreading murders, had been dispatched to Rome some time ago and were living under cover of the numerous Judaean community in Rome. The Judaeans are very zealous for their ancient religion. Despite the fact that there are so many schools of religious thought among them — the Nazarenes or Christians being but one — they all agree about the supreme majesty of their only God and are quite intractable in matters of religious images and making sacrifices to the traditional gods of Rome, let alone to the Emperor.

After the suspected terrorists were rounded up in such great numbers the anti-terrorism agencies had to turn the stadium into a maximum security detention and interrogation center, occasionally letting the populace in to witness how the terrorist threat was being tackled.

The leaders of the Christian sect protested that theirs is the religion of peace. But government spokespersons made it clear that it is high time that they stop covering the terrorists that hide within their community. Some independent stoic and epicurean intellectuals, together with the Greek non-imperial organisation Diethnika Amnēstiā decried the rising tide of “anti-Semitism” (using a stilted scholarly term referring to the common origin of most of the languages spoken in Judaea, and the Levant; we can safely bet that it will not stick).

It goes without saying that this undiscriminating, wholesale response under the vague bellum-ad-terrorem monicker is politically counterproductive, not to mention the appalling loss of innocent life and the racist overtones. As a consequence of the terrorist attacks on the capital, Roman security forces clamped down on Judaea and the whole region even further. It doesn’t take a training in aruspicine arcana to foretell that more trouble awaits Imperial rule in that benighted corner of the Middle East.

References

Acknowledgements

Cover image: Sirius, NASA/IPAC Infrared Science Archive (IRSA), image acquired at 3.368 microns wavelength. This publication makes use of data products from the Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer, which is a joint project of the University of California, Los Angeles, and the Jet Propulsion Laboratory/California Institute of Technology, funded by the National Aeronautics and Space Administration.

Still images taken from Barabbas (1961), motion picture directed by Richard Fleischer, featuring Anthony Quinn in the title role.

Originally published on securitypraxis.eu

Disclaimer: although based on historical data, the interpretation of events given in this post is largely fictional, and in any case it should not be construed as condoning any form of terrorism or showing lack of respect for the religious beliefs of the readers.

- Year DCCCXVII ab Urbe condita should correspond more or less to AD 64. ↩

- Tacitus, Annales, XV, 44.4. If we follow the fiction and assume that this is a report written shortly after the fire, this is obviously anachronistic. Let’s say that here we’re quoting Tacitus’ source material, now lost. ↩

- Josephus, The Jewish War, II.13.3 (emphasis added, and yes, another anachronism, and more below). ↩

- A Gothian author wrote an award-winning novel about Barabbas (brought to the big screen in a remarkable movie with Antonius Quinnius in the lead role). According to this novel, meeting Yeshua heNozri in person made quite an impression on Barabbas and he allegedly became one of his followers towards the end of his life. However, in this report we stick to the facts and not fictional romantic fantasies. ↩

- Gerhard J. Baudy, Die Brände Roms: ein apokalyptisches Motiv in der antiken Historiographie, Spudasmata Bd. 50, Hildesheim – Zürich – New York, 1991. ↩