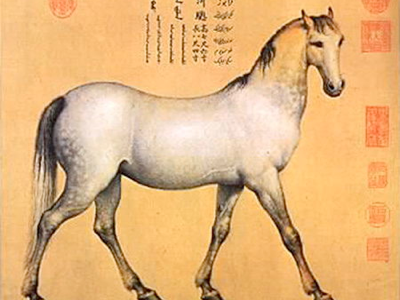

Afghan steeds at the Qing court

Happy New Year of the Horse!

Given my interest for Afghanistan I thought it fitting to celebrate the new Chinese year of the horse with these portraits of Afghan steeds, painted for the Qing emperor by the milanese Jesuit missionary artist Giuseppe Castiglione (Lang Shinin in pinyin) in the 18th century.

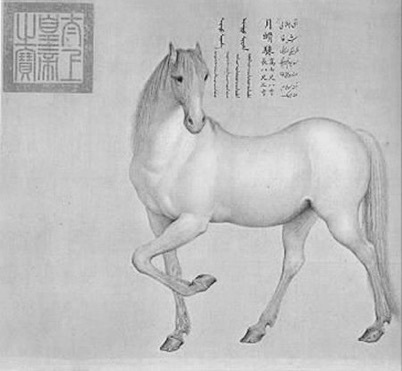

Horse Yuekulai (lit. Moon-bone Steed)

File:Horse Yuekulai.jpg – Wikimedia Commons

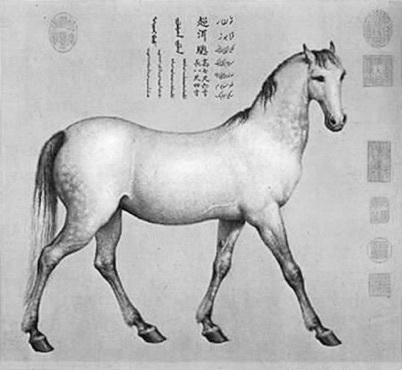

Horse Chaoni’er (lit. Exceeding Piebald)

File:Horse Chaoni’er.jpg – Wikimedia Commons

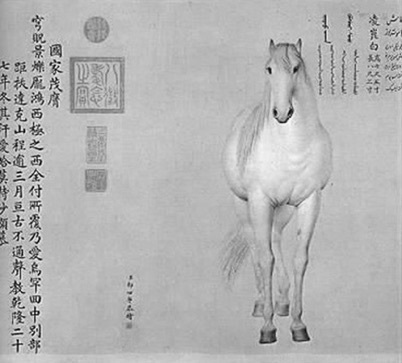

Horse Lingkunbai (lit. ice white)

File:Horse Lingkunbai.jpg – Wikimedia Commons

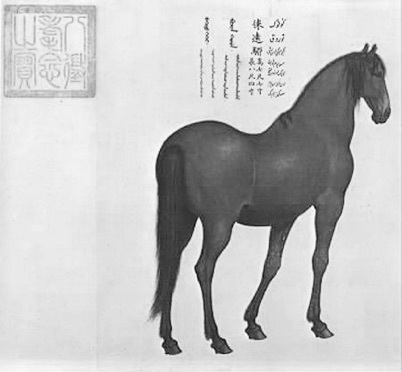

Horse Laiyuanliu (lit. Far-flung Bay)

File:Horse Laiyuanliu.jpg – Wikimedia Commons

In fact, I found the intersection of Afghan horses painted by an Italian Jesuit for the Chinese emperor particularly intriguing.

Central Asian horses have always been prized in China. Even throwing some healthy khaq on the 19th century glittering myth of the ‘Silk Road’ that keeps editors and writers so enamoured today, horses from Turkestan and che Oxus basin were an important part of Asian land trade. But very few of them had such a honour as to be portrayed by the official painter at the court of the Chinese emperor. So why were these horses so important or special, apart from their outstanding beauty?

I turned to a historian* to shed some tentative light on the story of these magnificent horses. The context is Qing expansion into Turkic Central Asia during the 18th century. The rising new emirate of Afghanistan under Ahmad Shah Durrani had his main ambitions trained towards the plains of Hindustan, but shifting power constellations on his northern flank were a matter of concern. It was a good moment to send an embassy and play nice with the new power of Central Asia.

<<Central Asian and Qing sources agree that in late 1762 Ahmad Shāh of Afghanistan had sent an embassy to Beijing. But while, according to the former, his intention was to address the emperor on the matter of Qing rule in Central Asia and to petition on behalf of the Āfāqī khoja house, Qing sources make no mention of any discussion on this subject.>>

Despite the fact that Qing chroniclers did not bother to record them, Ahmad Shah’s strategic aims appear quite sound: present himself and his empire as a relevant interlocutor, legitimising his role as advocate for the fellow Muslim dynasties that were being absorbed by Qing rule. As befits an ambitious state embassy, Ahmad Shah sent gifts worth of an Emperor that he knew would have been appreciated: <<The Afghan envoy presented the emperor with four splendid horses>>

Overall, the embassy had mixed results. Apparently the Emperor did not appreciate Ahmad Shah’s previous military and diplomatic forays in the region and strived to set the record straight as who’s who on the political chequerboard:

<<The Qianlong emperor took the opportunity of the audience to dispatch a letter to Ahmad Shāh in which he set out the empire’s expectations of the new Central Asian order. He commented the fact that on learning that Bukhara had already submitted to China (guifu Zhongguo) Ahmad Shāh had apparently called off his attack on the principality; however, noting with disapproval the details of Ahmad Shāh’s other recent military exploits, he instructed the Afghan ruler on the folly of war and concluded the missive with a reminder that he, the Qianlong emperor, was “the lord of all under Heaven (tianxia) who watches over everything inside and outside the empire and who rewards good and punishes evil.” He then ordered that letters to this effect should also be copied to the rulers of Badakhshan, Khoqand, the Edigene Qirghiz and the westerly Qazaqs of the Middle Horde.>>

More intriguingly, one of the reasons why the diplomatic mission did not succeed completely was that the Afghan envoy:

<<failed to make a good impression, not least because he refused to perform the kowtow. The court rapidly concluded that the Afghans were uncultured troublemakers who, in future, were not to be encouraged to send envoys to Beijing.>> […]

<<Of all the Muslim envoys who went to court at this time, only the Afghans appear to have refused to kowtow. Court officials angrily reprimanded the Afghan envoy, pointing out that even the Westerners and Russians had performed kowtow.>>

So it was not a simple matter of religion — other Muslims complied — or power, even the Westerners and Russians had no qualms in prostrating. No, despite everything, the Afghan would not yield, would not bow in front of the emperor. Having seen myself a little diplomatic show in reduced scale, I can almost picture the hardly controlled frustration mounting on the faces of the cultured and sophisticated court officials in front of such unreasonable stubbornness. If something like the ‘Afghan character’ ever existed, it manifested here at its best.

Happy new year of the horse!

* L. J. Newby, The Empire and the Khanate: A Political History of Qing Relations with Khoqand C. 1760-1860, Brill, 2005, pp. 35-36.

(The original paintings of the Afghan steeds are kept at the National Palace Museum in Taiwan.)